A Neuro-Symbolic Framework for Large Language Models

Project description

SymbolicAI

A Neuro-Symbolic Perspective on Large Language Models (LLMs)

Building applications with LLMs at the core using our Symbolic API facilitates the integration of classical and differentiable programming in Python.

What is SymbolicAI?

Conceptually, SymbolicAI is a framework that leverages machine learning – specifically LLMs – as its foundation, and composes operations based on task-specific prompting. We adopt a divide-and-conquer approach to break down a complex problem into smaller, more manageable problems. Consequently, each operation addresses a simpler task. By reassembling these operations, we can resolve the complex problem. Moreover, our design principles enable us to transition seamlessly between differentiable and classical programming, allowing us to harness the power of both paradigms.

Installation

Core Features

To get started with SymbolicAI, you can install it using pip:

pip install symbolicai

Setting up a neurosymbolic API Key

Before using SymbolicAI, you need to set up API keys for the various engines. Currently, SymbolicAI supports the following neurosymbolic engines through API: OpenAI, Anthropic. We also support {doc}local neurosymbolic engines <ENGINES/local_engine>, such as llama.cpp and huggingface.

# Linux / MacOS

export NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY="…"

export NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_MODEL="…"

# Windows (PowerShell)

$Env:NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY="…"

$Env:NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_MODEL="…"

# Jupyter Notebooks

%env NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY=…

%env NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_MODEL=…

Optional Features

SymbolicAI uses multiple engines to process text, speech and images. We also include search engine access to retrieve information from the web. To use all of them, you will need to also install the following dependencies and assign the API keys to the respective engines.

pip install "symbolicai[wolframalpha]"

pip install "symbolicai[whisper]"

pip install "symbolicai[selenium]"

pip install "symbolicai[serpapi]"

pip install "symbolicai[pinecone]"

Or, install all optional dependencies at once:

pip install "symbolicai[all]"

And export the API keys, for example:

# Linux / MacOS

export SYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY="<WOLFRAMALPHA_API_KEY>"

export SEARCH_ENGINE_API_KEY="<SERP_API_KEY>"

export OCR_ENGINE_API_KEY="<APILAYER_API_KEY>"

export INDEXING_ENGINE_API_KEY="<PINECONE_API_KEY>"

# Windows (PowerShell)

$Env:SYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY="<WOLFRAMALPHA_API_KEY>"

$Env:SEARCH_ENGINE_API_KEY="<SERP_API_KEY>"

$Env:OCR_ENGINE_API_KEY="<APILAYER_API_KEY>"

$Env:INDEXING_ENGINE_API_KEY="<PINECONE_API_KEY>"

See below for the entire list of keys that can be set via environment variables or a configuration file.

Additional Requirements

SpeechToText Engine: Install ffmpeg for audio processing (based on OpenAI's whisper)

# Linux

sudo apt update && sudo apt install ffmpeg

# MacOS

brew install ffmpeg

# Windows

choco install ffmpeg

WebCrawler Engine: For selenium, we automatically install the driver with chromedriver-autoinstaller. Currently we only support Chrome as the default browser.

Configuration Management

SymbolicAI now features a configuration management system with priority-based loading. The configuration system looks for settings in three different locations, in order of priority:

-

Debug Mode (Current Working Directory)

- Highest priority

- Only applies to

symai.config.json - Useful for development and testing

-

Environment-Specific Config (Python Environment)

- Second priority

- Located in

{python_env}/.symai/ - Ideal for project-specific settings

-

Global Config (Home Directory)

- Lowest priority

- Located in

~/.symai/ - Default fallback for all settings

Configuration Files

The system manages three main configuration files:

symai.config.json: Main SymbolicAI configurationsymsh.config.json: Shell configurationsymserver.config.json: Server configuration

Viewing Your Configuration

Before using the package, we recommend inspecting your current configuration setup using the command below. This will create all the necessary configuration files.

symconfig

This command will show:

- All configuration locations

- Active configuration paths

- Current settings (with sensitive data truncated)

Configuration Priority Example

my_project/ # Debug mode (highest priority)

└── symai.config.json # Only this file is checked in debug mode

{python_env}/.symai/ # Environment config (second priority)

├── symai.config.json

├── symsh.config.json

└── symserver.config.json

~/.symai/ # Global config (lowest priority)

├── symai.config.json

├── symsh.config.json

└── symserver.config.json

If a configuration file exists in multiple locations, the system will use the highest-priority version. If the environment-specific configuration is missing or invalid, the system will automatically fall back to the global configuration in the home directory.

Best Practices

- Use the global config (

~/.symai/) for your default settings - Use environment-specific configs for project-specific settings

- Use debug mode (current directory) for development and testing

- Run

symconfigto inspect your current configuration setup

This addition to the README clearly explains:

- The priority-based configuration system

- The different configuration locations and their purposes

- How to view and manage configurations

- Best practices for configuration management

Configuration File

You can specify engine properties in a symai.config.json file in your project path. This will replace the environment variables. The default configuration file that will be created is:

{

"NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY": "",

"NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_MODEL": "",

"SYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY": "",

"SYMBOLIC_ENGINE": "",

"EMBEDDING_ENGINE_API_KEY": "",

"EMBEDDING_ENGINE_MODEL": "",

"DRAWING_ENGINE_MODEL": "",

"DRAWING_ENGINE_API_KEY": "",

"SEARCH_ENGINE_API_KEY": "",

"SEARCH_ENGINE_MODEL": "",

"INDEXING_ENGINE_API_KEY": "",

"INDEXING_ENGINE_ENVIRONMENT": "",

"TEXT_TO_SPEECH_ENGINE_MODEL": "",

"TEXT_TO_SPEECH_ENGINE_API_KEY": "",

"SPEECH_TO_TEXT_ENGINE_MODEL": "",

"VISION_ENGINE_MODEL": "",

"OCR_ENGINE_API_KEY": "",

"COLLECTION_URI": "",

"COLLECTION_DB": "",

"COLLECTION_STORAGE": "",

"SUPPORT_COMMUNITY": false,

}

Example of a configuration file with all engines enabled:

{

"NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY": "<OPENAI_API_KEY>",

"NEUROSYMBOLIC_ENGINE_MODEL": "gpt-4o",

"SYMBOLIC_ENGINE_API_KEY": "<WOLFRAMALPHA_API_KEY>",

"SYMBOLIC_ENGINE": "wolframalpha",

"EMBEDDING_ENGINE_API_KEY": "<OPENAI_API_KEY>",

"EMBEDDING_ENGINE_MODEL": "text-embedding-3-small",

"DRAWING_ENGINE_API_KEY": "<OPENAI_API_KEY>",

"DRAWING_ENGINE_MODEL": "dall-e-3",

"VISION_ENGINE_MODEL": "openai/clip-vit-base-patch32",

"SEARCH_ENGINE_API_KEY": "<PERPLEXITY_API_KEY>",

"SEARCH_ENGINE_MODEL": "llama-3.1-sonar-small-128k-online",

"OCR_ENGINE_API_KEY": "<APILAYER_API_KEY>",

"SPEECH_TO_TEXT_ENGINE_MODEL": "turbo",

"TEXT_TO_SPEECH_ENGINE_MODEL": "tts-1",

"INDEXING_ENGINE_API_KEY": "<PINECONE_API_KEY>",

"INDEXING_ENGINE_ENVIRONMENT": "us-west1-gcp",

"COLLECTION_DB": "ExtensityAI",

"COLLECTION_STORAGE": "SymbolicAI",

"SUPPORT_COMMUNITY": true

}

With these steps completed, you should be ready to start using SymbolicAI in your projects.

[NOTE]: Our framework allows you to support us train models for local usage by enabling the data collection feature. On application startup we show the terms of services and you can activate or disable this community feature. We do not share or sell your data to 3rd parties and only use the data for research purposes and to improve your user experience. To change this setting open the

symai.config.jsonand turn it on/off by setting theSUPPORT_COMMUNITYproperty toTrue/Falsevia the config file or the respective environment variable. [NOTE]: By default, the user warnings are enabled. To disable them, exportSYMAI_WARNINGS=0in your environment variables.

Quick Start Guide

This guide will help you get started with SymbolicAI, demonstrating basic usage and key features.

To start, import the library by using:

from symai import Symbol

Creating and Manipulating Symbols

Our Symbolic API is based on object-oriented and compositional design patterns. The Symbol class serves as the base class for all functional operations, and in the context of symbolic programming (fully resolved expressions), we refer to it as a terminal symbol. The Symbol class contains helpful operations that can be interpreted as expressions to manipulate its content and evaluate new Symbols <class 'symai.expressions.Symbol'>.

# Create a Symbol

S = Symbol("Welcome to our tutorial.")

# Translate the Symbol

print(S.translate('German') # Output: Willkommen zu unserem Tutorial.

Ranking Objects

Our API can also execute basic data-agnostic operations like filter, rank, or extract patterns. For instance, we can rank a list of numbers:

# Ranking objects

import numpy as np

S = Symbol(np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]))

print(S.rank(measure='numerical', order='descending')) # Output: ['7', '6', '5', '4', '3', '2', '1']

Evaluating Expressions

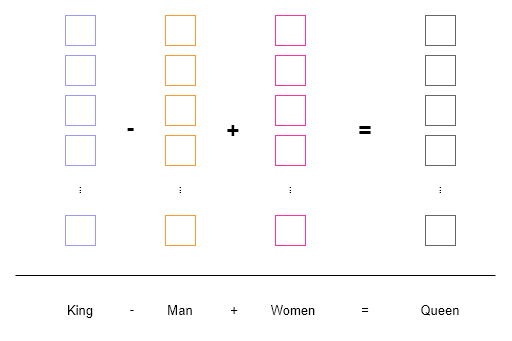

Evaluations are resolved in the language domain and by best effort. We showcase this on the example of word2vec.

Word2Vec generates dense vector representations of words by training a shallow neural network to predict a word based on its neighbors in a text corpus. These resulting vectors are then employed in numerous natural language processing applications, such as sentiment analysis, text classification, and clustering.

In the example below, we can observe how operations on word embeddings (colored boxes) are performed. Words are tokenized and mapped to a vector space where semantic operations can be executed using vector arithmetic.

Similar to word2vec, we aim to perform contextualized operations on different symbols. However, as opposed to operating in vector space, we work in the natural language domain. This provides us the ability to perform arithmetic on words, sentences, paragraphs, etc., and verify the results in a human-readable format.

The following examples display how to evaluate such an expression using a string representation:

# Word analogy

S = Symbol('King - Man + Women').interpret()

print(S) # Output: Queen

Dynamic Casting

We can also subtract sentences from one another, where our operations condition the neural computation engine to evaluate the Symbols by their best effort. In the subsequent example, it identifies that the word enemy is present in the sentence, so it deletes it and replaces it with the word friend (which is added):

# Sentence manipulation

S = Symbol('Hello my enemy') - 'enemy' + 'friend'

print(S) # Output: Hello my friend

Additionally, the API performs dynamic casting when data types are combined with a Symbol object. If an overloaded operation of the Symbol class is employed, the Symbol class can automatically cast the second object to a Symbol. This is a convenient way to perform operations between Symbol objects and other data types, such as strings, integers, floats, lists, etc., without cluttering the syntax.

Probabilistic Programming

In this example, we perform a fuzzy comparison between two numerical objects. The Symbol variant is an approximation of numpy.pi. Despite the approximation, the fuzzy equals == operation still successfully compares the two values and returns True.

# Fuzzy comparison

S = Symbol('3.1415...')

print(S == np.pi) # Output: True

🧠 Causal Reasoning

The main goal of our framework is to enable reasoning capabilities on top of the statistical inference of Language Models (LMs). As a result, our Symbol objects offers operations to perform deductive reasoning expressions. One such operation involves defining rules that describe the causal relationship between symbols. The following example demonstrates how the & operator is overloaded to compute the logical implication of two symbols.

S1 = Symbol('The horn only sounds on Sundays.', only_nesy=True)

S2 = Symbol('I hear the horn.')

(S1 & S2).extract('answer') # Since I hear the horn, and the horn only sounds on Sundays, it must be Sunday.

Note: The first symbol (e.g.,

S1) needs to have theonly_nesyflag set toTruefor logical operators. This is because, without this flag, the logical operators default to string concatenation. While we didn't find a better way to handle meta-overloading in Python, this flag allows us to use operators like'A' & 'B' & 'C'to produce'ABC'or'A' | 'B' | 'C'to result in'A B C'. This syntactic sugar is essential for our use case.

The current & operation overloads the and logical operator and sends few-shot prompts to the neural computation engine for statement evaluation. However, we can define more sophisticated logical operators for and, or, and xor using formal proof statements. Additionally, the neural engines can parse data structures prior to expression evaluation. Users can also define custom operations for more complex and robust logical operations, including constraints to validate outcomes and ensure desired behavior.

🪜 Next Steps

This quick start guide covers the basics of SymbolicAI. We also provide an interactive notebook that reiterates these basics. For more detailed information and advanced usage explore the topics and tutorials listed below.

- More in-depth guides: {doc}

Tutorials <TUTORIALS/index> - Using different neuro-symbolic engines: {doc}

Engines <ENGINES/index> - Advanced causal reasoning: {doc}

Causal Reasoning <FEATURES/causal_reasoning> - Using operations to customize and define api behavior: {doc}

Operations <FEATURES/operations> - Using expressions to create complex behaviors: {doc}

Expressions <FEATURES/expressions> - Managing modules and imports: {doc}

Import Class <FEATURES/import> - Error handling and debugging: {doc}

Error Handling and Debugging <FEATURES/error_handling> - Built-in tools: {doc}

Tools <TOOLS/index>

Contribution

If you wish to contribute to this project, please refer to the docs for details on our code of conduct, as well as the process for submitting pull requests. Any contributions are greatly appreciated.

📜 Citation

@software{Dinu_SymbolicAI_2022,

author = {Dinu, Marius-Constantin},

editor = {Leoveanu-Condrei, Claudiu},

title = {{SymbolicAI: A Neuro-Symbolic Perspective on Large Language Models (LLMs)}},

url = {https://github.com/ExtensityAI/symbolicai},

month = {11},

year = {2022}

}

📝 License

This project is licensed under the BSD-3-Clause License - refer to the docs.

Like this Project?

If you appreciate this project, please leave a star ⭐️ and share it with friends and colleagues. To support the ongoing development of this project even further, consider donating. Thank you!

We are also seeking contributors or investors to help grow and support this project. If you are interested, please reach out to us.

📫 Contact

Feel free to contact us with any questions about this project via email, through our website, or find us on Discord:

To contact me directly, you can find me on LinkedIn, Twitter, or at my personal website.